I can hear a noise. It’s repetitive, but I can’t quite figure out what it is and why it won’t stop.

Bleary-eyed, I finally realise it’s my alarm. A quick squint reveals the unsociable hour of 3am and it’s then I remember I’ve agreed with myself that getting up at this time in the morning is a good idea. At this moment it feels far removed from a good idea.

As I stumble out of bed and into the kitchen there is already light in the sky and the rather harsh and jangly song of song thrush permeates from somewhere behind the shed. Knowing that I’m not my sharpest at this time of the morning I’m rather pleased with myself when I see that I’d already laid out the coffee pot and porridge bowl the night before in anticipation of getting going.

Why bother getting up at this hour at all? Put simply, it’s the light. I’ve started work on a new volume of ‘Naturally Orkney’ and I’m currently concentrating on the waders who call our farmland their homes. This is a very busy time of year for them and there will be all kind of stages of breeding, birds incubating eggs and those already with young. The weather has been kind of late with clear skies, the cold winds of the north east replaced with milder temperatures. This means the light I like, those with warmer hues, soon turn to something altogether brighter and blown out an hour or two after sunrise. Sunrise happens to be creeping ever closer to 4am now and so when the alarm goes off it’s either commit to getting up or just go back to sleep.

There really is only one way to photograph waders at close quarters and that is to use a hide. My hide is on a farm in South Ronaldsay and as I drive across the Churchill Barriers the water is eerily still around the blockships, the peach-coloured sky reflected in the sea.

I had placed my hide next to a muddy pool some weeks earlier in a field that is due to be grazed by cattle later in the month. Ideally, I would like to get in whilst it’s dark but at this time of year that’s not possible, once I’m in however it doesn’t take long for the birds to settle down again. This farm has a good number of breeding waders and I know from previous years that they like the varied fields here, some on the agri-environment scheme, some not.

Waders are by their very nature attracted to wet areas and so the pool seemed a good bet for getting some nice close-up shots as it’s the only standing source of mud and water for quite a distance. Different waders like different things however and not every field ticks the boxes for all species. The next field over for instance was barley last year and so is already short in terms of vegetation length. This is where the lapwings have nested this year, three pairs, I think. This is ideal for them as they don’t like fields with tall or heavy grass cover. They also like to nest in loose colonies and so with perhaps another three or four pairs in adjacent fields I have a lot of hope for them this year.

Oystercatchers are nesting in this field too, much to the ire of the lapwings who seem to take umbrage at their presence as much as they do the odd hooded crow that flies overhead.

Once in the hide I make life as easy as I can for myself. I have a therma-rest laid out from head to toe to give myself something cushioned to sit on or lie down if I need to. This hide is a different design from my usual standard design, similar but longer and lower. I’ve also brought a flask of coffee and some snacks and an extra layer of clothing should I need it.

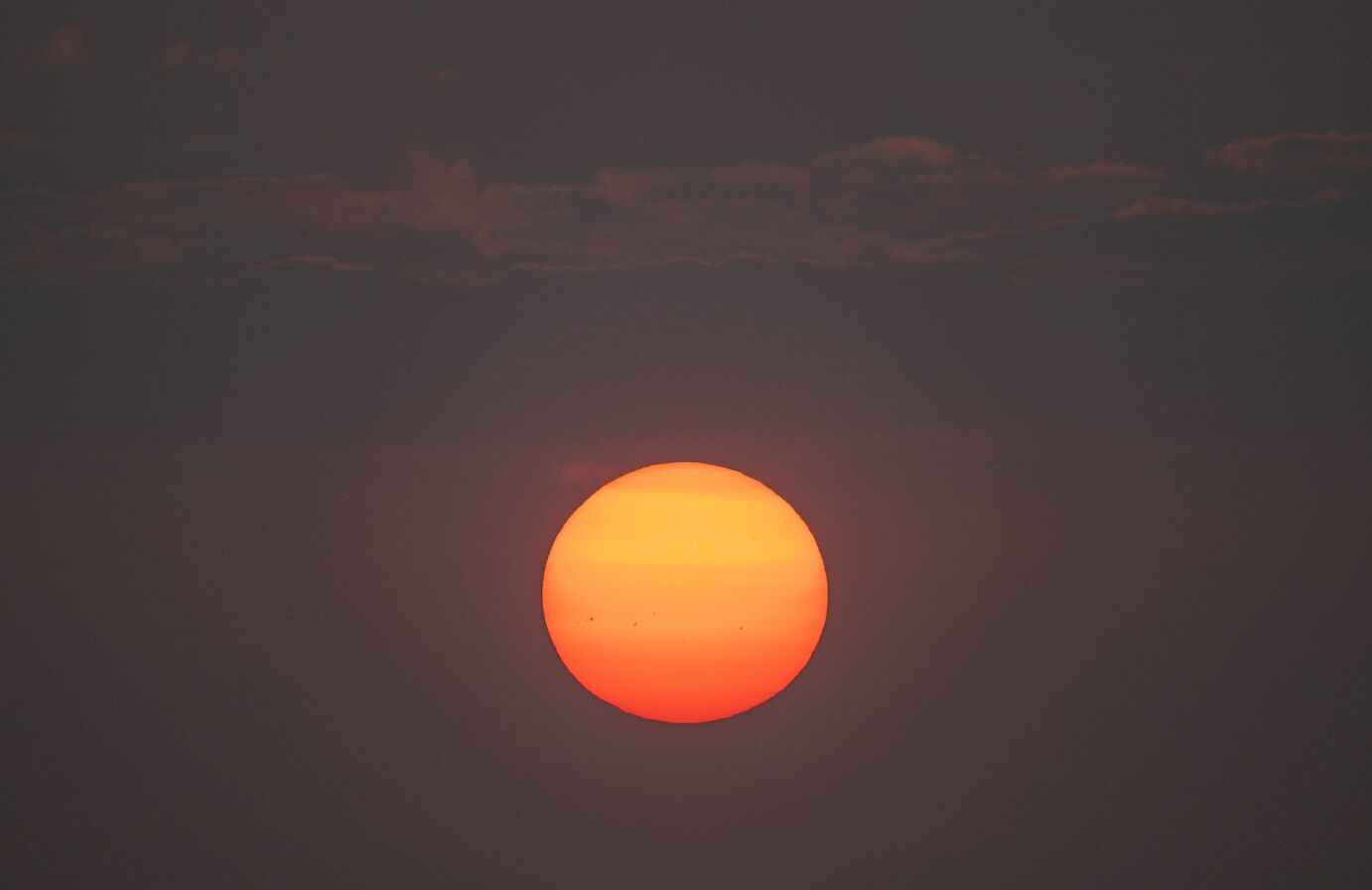

Facing east, I can just make out the shape of Copinsay on the horizon, merely a darker shade of grey against the North Sea. But it’s not long before there’s a shimmer of red and once the sun has risen properly it’s a deep orange colour. There is a breath of wind, only just, but enough for the water in the pool to ripple a little, but it ripples gold. It’s not long before the first visitor to this golden pool lands along its edge, with its simple call, ‘tew-ew-ew’. I recognise it instantly as a redshank.

Everything about this bird can be described as medium. Medium length bill, medium length legs and, well, it’s a medium-sized bird. It has a brighter, bolder version of its winter plumage now and as its name suggests its most distinctive feature is its bright orange-red legs with the base of its bill matching this colour.

Moments later another redshank lands and starts circumnavigating its way around the muddy edge of the pool, probing and feeding as it goes, picking up some sort of invertebrate, disturbing small clouds of flies as the mud slips from its orange ‘shanks’. The first redshank fastidiously preens its feathers, in fact I don’t think I’ve seen any other species pay such particular and dedicated attention to keeping its plumage clean. Its focus is broken however at the arrival of first two, then three more redshanks. For a chaotic moment there are redshank chasing each other through the water, alighting and landing before chasing each other off again. This pool is clearly an important commodity within the breeding territory of the waders and worth fighting over.

As they fly off, I see the white triangular rump patch common to many waders. If you’re in any doubt as to whether you’ve seen a redshank then the white triangles on the trailing edges of the wings will confirm your suspicions.

Whilst it is relatively easy to spot a nesting lapwing or oystercatcher, the redshank is an altogether more difficult proposition. They tend not to nest in the open but rather within a tussock of grass itself, with a small opening to a shallow scrape with three or four darkly speckled eggs inside. Both parents will incubate the eggs which will hatch after around three and a half weeks. It is then that this most Jekyll and Hyde of waders changes character, gone are its secretive nesting habits, replaced by a very public display of alarm and noise should anyone or anything come too close to where its chicks might be hiding.

It puts the multitude of Orcadian fence posts to good use, bobbing up and down from the perfect vantage point to monitor the whereabouts of its chicks and a handy place to yell ‘danger’ to all the birds in the area. This extreme alertness has earned it the name ‘sentinel of the marsh’. Read about the redshank in any bird book and the language used to describe it when alarmed is rather unflattering - ‘hysterical’ or ‘neurotic’. But this feels rather mean and I prefer its Orcadian name of ‘watery pleeps’. I love the word ‘pleep’, it means to whine or complain and is usually used by someone who is somewhat exasperated – as in ‘oh, stop pleepin!’ - or to describe someone who moans and complains about trivial things - ‘what a pleep they are’.

They aren’t the only birds at the pool however and over the course of the last three weeks it’s been used for feeding and washing by 15 different species. They range in size from shelduck to the diminutive skylark. After a few hours I lie back and rest my head on the bucket of empty sheep feed I’ve borrowed from the farmhouse and listen to the skylark overhead. I can honestly say that in the bubble of the hide, in these early hours surrounded by the calls of some of our most familiar birds, I’m as happy as I’ve ever been.

Another secretive bird makes a comical side entrance. A snipe has landed on the top of the hide and belts out its repetitive call, it must be only six inches above me.

When I lift my head to make sure I’m not missing out on anything I see that both a curlew and lapwing have silently made their way into the water and are cleaning themselves. Both these species have seen dramatic declines in their numbers not only across the UK but in Orkney too. Many things contribute to whether a wader has a successful breeding season or not - bad weather, predation by both avian and mammal predators (most likely stoats in Orkney), and mostly where the wader decides to nest during the spring. If that’s on farmland, it’s dependent on what the intended use of the field is that year.

As this farm proves they can be successful but it’s not too controversial to say that intensive practices are to the detriment of wader populations. Our wader numbers are still healthy enough that with the right conditions created for them they can bounce back quickly, as has been shown in recent projects in the north isles such as Wyre and North Ronaldsay. In some of these cases fallow land has been brought back into production with the introduction of lighter cattle to graze and break up the vegetation. A win for the birds, land and farmer.

The birds on this farm (and many others across Orkney) are lucky in that the farmer and his family look out for nests and chicks whilst working the land and that the land itself is a mosaic of different habitats, with the different vegetation lengths the different waders need.

These birds aren’t just important on their own merit but they are also part of our language, and if we lose them, not only do we lose the soundtrack of our landscape but we lose something of our Orcadian tongue too. Very few people in Orkney would call a hen harrier a ‘katabelly’ anymore, but the use of ‘teeick’ & ‘teeo’, and even more specifically ‘theevnick’ in South Ronaldsay (lapwing), and ‘whaap’ or ‘whaup’ (curlew) are still commonplace.

Let’s keep an eye on them, encourage them to grow to their former numbers, and enjoy the tumbling teeo and bubbling whaup. Let’s celebrate that peedie orange-legged pleep noisily scolding us, their racket a sign of their success at hatching their chicks for another spring.

Raymond is a wildlife filmmaker who also offers bespoke Orkney wildlife tours and one-to-one wildlife photography tuition. Find out more via his official website. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.