“I actually started trying to play the violin back in the early 1990s and didn’t get on very successfully,” recalls Colin Tulloch. “I then decided to start making them instead.”

Whatever the music world lost in terms of a potential performer it has gained tenfold from Colin Tulloch’s skills as a violin maker. The Kirkwall based craftsman’s instruments are now held in the highest regard by the finest of international musicians.

“I got hold of a book on violin making when I was working in engineering in Edinburgh,” explains Colin, who setup Tulloch Violins around 20 years ago. “I made the first violin with virtually no tuition from anybody at all and got a result sound wise. I started building up tools and, as time went on, I made more instruments. Then some of the good players in Orkney played them, so that was an encouragement I was doing something right. To turn out something that somebody really appreciates and loves is great.”

From the outset, Colin sought to follow the example of the most famous makers of Italy’s Cremona province - Amati, Stradivari, Guarneri and Bergonzi.

But high-end Cremonese style violin making has long been a secretive and close-knit world in which arcane knowledge of design, construction techniques, woods and varnishes is passed down over the centuries, through families and between a succession of masters and apprentices.

For Colin, that vital insight into the Cremonese arts was to come through the most remarkable of genealogical coincidences - one with the island of North Ronaldsay at its heart, rather than Italy.

In the late 1990s, Colin discovered that he shared a North Ronaldsay ancestor with leading American violin maker, Kelvin Scott - a former pupil of the internationally renowned master, Gregg Alf.

When Colin and Kelvin finally met in 2002, thanks to another mutual relative, Kelvin immediately recognised Colin’s enormous potential and natural ability. Kelvin subsequently invited Colin to the USA to study alongside him and benefit from his formal training in the Italian methods of violin making. Energised by their shared love of Cremona and Orkney, Colin and Kelvin collaborated on a number of projects and continue to do so today.

And, true to those old family traditions in violin making, Colin is now passing on that knowledge to his son Findlay, who has joined him in the business.

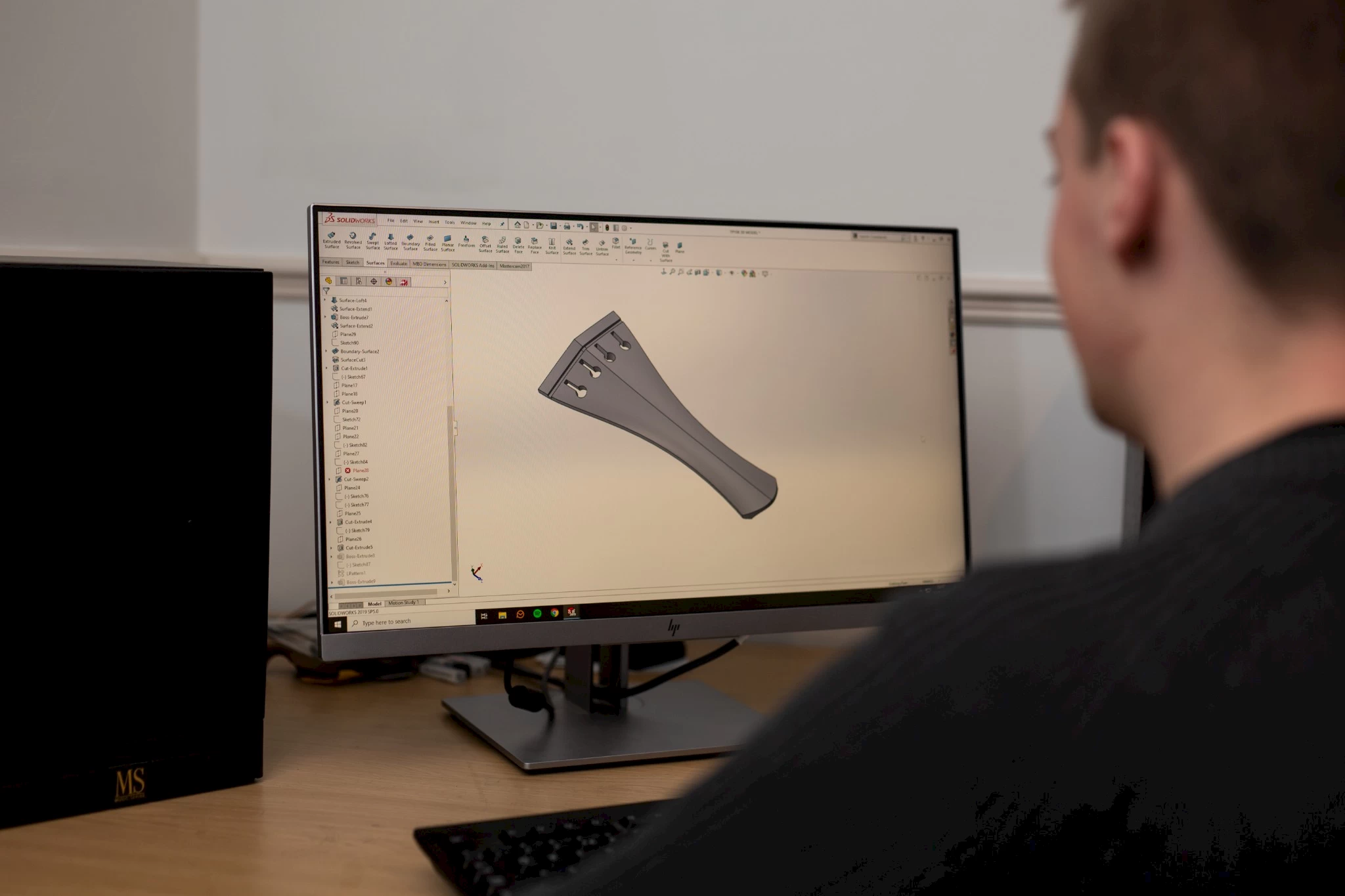

But 22-year-old Findlay is proving to be much more than mere workshop apprentice, with his expertise in computer aided design now bringing a new high-tech dimension to Tulloch Violins.

Father and son recently invested in a state-of-the-art CNC milling machine, one specially made to precision cut wood and light metal, and they’re now exploring its potential for creating high quality instrument fittings – most notably violin tailpieces - along with specialised tools, jigs and templates.

“We’re at the infancy stage, but are getting some good results with the fittings,” says Colin. “If we were to make violin tailpieces by hand, which we could do, they’d be far too expensive to sell to anybody.

“We sent a sample tailpiece to one of the leading violin makers in London who came back with extremely good feedback and some constructive comments,” explains Colin. “We then altered the design two or three times until we came up with the right tailpiece. Findlay’s spent hours and hours at the computer, doing all the programming for the milling machine, and we’re now producing a series of tailpieces in sustainably sourced sourced English boxwood and African blackwood.”

Findlay’s been around his father’s workshop for most of his life, seeing violins taking shape and helping with traditional processes like varnish cooking, but he’d never envisaged actually becoming a partner in the business.

“I went to do computer aided architectural design and technology in Glasgow, but didn’t really enjoy it,” says Findlay. “I then returned to Glasgow to do an intensive course on computer aided design. I’d always been involved with Dad’s work, but the new machine has made it more interesting for me and I really want to see what I can do to help develop the business.”

It’s not all computer based work for Findlay though. He made his first violin during last year’s lockdown, working side by side with his father, and his second is now underway. It’s also clear he’s got the bug for handcrafting quality instruments.

“Making the first violin was quite a big learning curve, but there was real sense of achievement getting it finished,” says Findlay. “It’s becoming a more familiar process now I’m on my second. I think once our fittings and other products made on the CNC machine are developed a bit further, all that will run in the background and I can concentrate more on the violin making.”

Colin’s been impressed by his son’s efforts too and he’s enjoying the opportunity to pass on his knowledge. “I put Findlay’s first violin beside two I’d made during lockdown and there was virtually no difference in the sound,” says Colin, who takes around 140 hours to create one of his much sought after instruments.

“It’s about going through a system,” he continues. “We carefully select the right woods - European spruce, maple and sometimes Scottish sycamore – check the weights, look at how the plates will work together and decide what’s best in terms of varnish and pigments. The system is quite strict, with tolerances we work within so we know we’re going to get repeatability.”

Colin’s also following his own learning curve having branched out into making cellos, a process he describes as “more of an unknown”, but again it’s that North Ronaldsay connection that’s been helping him along.

“When it came to making my first cello I went back across to the USA and Kelvin and myself each made one, side by side at the bench,” says Colin. “I came back from that trip with measurements for all the jigs, and Findlay’s now programmed the computer to create cello templates we can produce on the milling machine.”

These are, of course, uncertain times for musicians worldwide, with concert venues closed, orchestra rehearsals and tours shelved, festivals cancelled and opportunities to perform limited to online only. Unsurprisingly, that has had a ripple effect on sales across the entire instrument making community, though Colin remains optimistic about the future.

“It’s taken the edge off as musicians are not moving about, not playing concerts and probably not thinking about new instruments, but I’m looking beyond that,” he says. “I know that this is going to resolve itself, so in a lot of ways we’ve made the best of it, developing fittings and making the finest instruments we can. We’ve stayed extremely positive and know the storm will pass.”

Visit the official Colin Tulloch Violins website. You can also see more of Colin and Findlay's work on Instagram and Facebook.