There is nothing else like the Dwarfie Stane in all of Britain, and almost nothing about it is certain.

This leaves the door wide open for tall tales – dwarves, giants, faerie folk, and much more besides. These are just a few of the Dwarfie Stane’s stories.

Dispelling the magic just before ramping it up, the Dwarfie Stane in Hoy is a 28 foot-long block of red sandstone known as a glacial erratic. This means it was dropped by retreating glaciers as they scoured the land during the end of the last Ice Age. There it laid for thousands of years until the 3rd Millennium BC, when it was carved out like a stone pumpkin with tools of antler and stone and monumental patience.

An intimate connection with its creators can be seen in the form of tool marks still visible on its roof. Inside it has a central passage with two a small dome-like chamber on either side, one containing a carved stone ‘bed’ complete with stone pillow.

Local lore holds that this was the work and home of giants. Already we have our first mystery, as anyone who has seen it will know that no giant worthy of the title could ever fit inside!

Still, it is said that a giant and his pregnant wife once inhabited the Stane. Its comforts were the envy of a neighbouring giant who, abiding by the adage of ‘if I can’t have it, no one can’, climbed atop the Dwarfie Hamars and hurled a stone down towards it. This blocked the entrance passage, trapping the couple within. The giant husband used his great strength to burst out of the top and chased the assailant down to an unknown end. Indeed, at some point the roof was broken through, and a stone blocked the entrance into the 16th century but was shifted out some time thereafter.

Walter Scott visited the Dwarfie Stane and wove his Romantic magic, describing it as “hewn by no earthly hand” and, delightfully, as “that wonderful carbuncle.” Sure enough, its appearance from a distance and especially from above is distinctly like that of a barnacle stuck to the thin soils at the base of the Dwarfie Hamars. In The Pirate, Scott envisioned it as the home of a Trolld, “a dwarf famous in the northern sagas.” According to Scott, shepherds avoided it due to its mythical inhabitant, described as a “necromantic owner” of great power and terror. His silhouette could be seen at sunrise and sunset sitting outside the Stane’s entrance.

Not knowing of Scott’s visit at the time of my own, I found it an ideal place at which to write. Sitting cross-legged and slightly hunched within its chamber and then upon the stone outside its entrance, for several hours words flowed with ease into my notebook - a first attempt at a new mythology for its origins in the deep mists of time. But that is a story for another day.

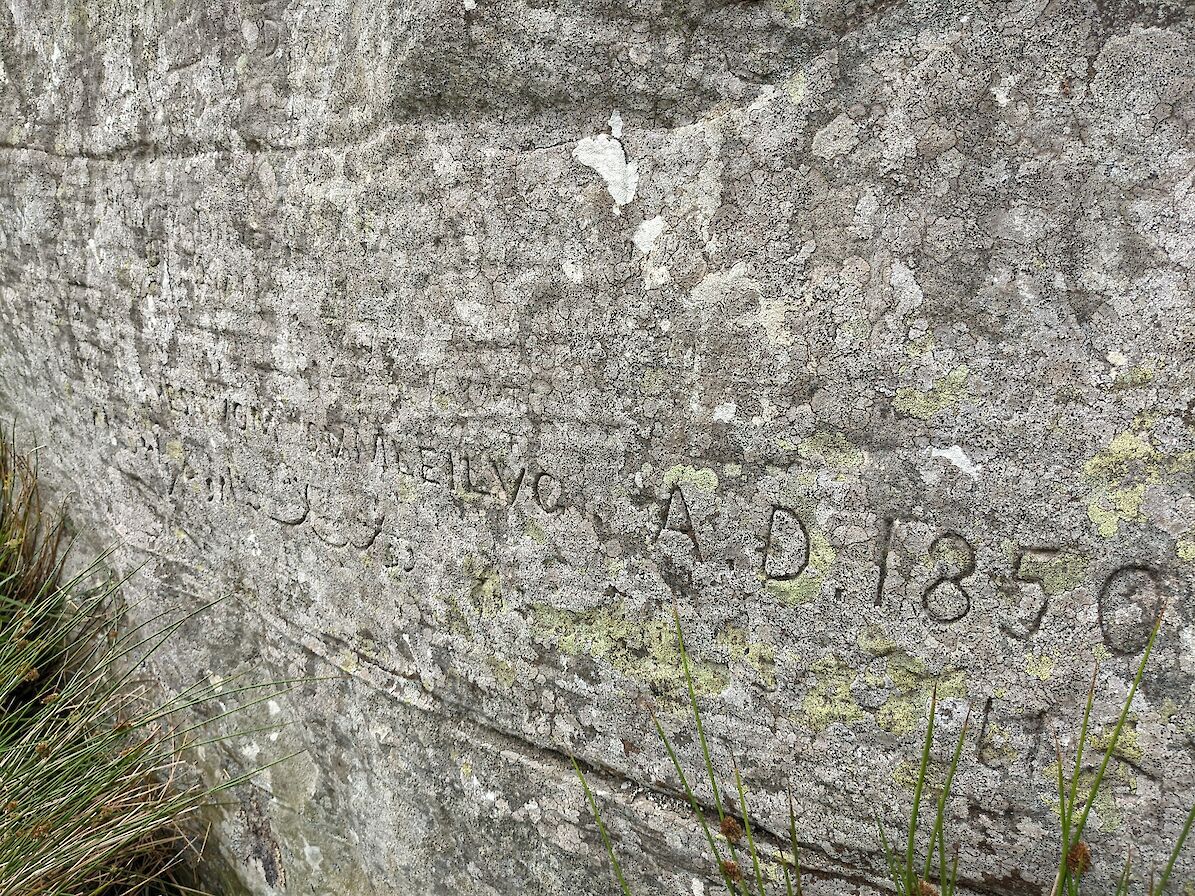

Visiting several decades after the publication of The Pirate, Scott’s horror twist on the Dwarfie Stane did not deter Major William Mounsey. Mounsey was an eccentric solicitor from Cumbria who served the British Empire in Persia as a spy. He left stylised graffiti on many ancient monuments along the River Eden, though the double inscription he made on the south face of the Dwarfie Stane - another practice no others should follow - is perhaps his most famous. In Persian and reversed Latin it reads (translated), “I have sat two nights and so learnt patience”. This may mean he used it is a hermitage for meditation or, speaking from personal experience, endured the local midges.

In The Trowies of Trowie Glen, Orcadian storyteller Tom Muir relates the tale of Mansie Rich. Mansie was a Rackwick man, who one day was “overcome by a strange feeling…drawn by some mysterious force to the head of Trowie Glen.” There he saw a procession of peedie folk (‘peedie’ is Scots for ‘small’), no more than a foot tall, marching into the glen to meet ‘Himself’. Himself was their leader, slightly taller than the rest with a pointed white beard and dressed in a blue velvet robe and turban. Mansie met Himself, but when he lit the tobacco in his pipe thinking it would impress his magical hosts the peedie folk choked and writhed on the cave’s floor. In an instant Mansie was ejected from the cave, with all trace of it vanished and the peedie folk fallen silent.

Like Mansie, I too fell prey to the hypnotic magnetism of Trowie Glen. Looking at the nearly sheer face of the Dwarfie Hamars immediately behind the Dwarfie Stane, I wondered if any ancient peoples left their marks on the stones there. Climbing up just a little, hoping to spot cup marks or other long-hidden symbols, an irresistible compulsion drove me up, up, up, always - so I told myself - just to the next stone, then I would turn back. Before I knew it, I had scaled the Hamars entirely and looked down from their crest, winded but exhilarated. In hindsight and with an appreciation for the Hamars’ perils, I can scarcely believe I made it; yet at the time, it felt as natural and necessary as taking my next breath. I later learned that the Hamars are now home to breeding white-tailed eagles who need to be left well enough alone, so if you visit then please do not follow in my entranced footsteps.

Without thinking and without prior knowledge of the area I skewed down into the embrace of Trowie Glen proper. Forced to return to my rucksack at the Dwarfie Stane by diabetic needs, the glen’s slopes slowly released me. At its mouth is another massive glacial erratic called the Partick Stane, which has been adorned with wooden placards on posts painted to resemble a door and two windows. The trowies are long gone from Trowie Glen, if the stories are to be believed, but there is still something strange and playfully revelrous at work here.

Intriguingly, Rackwick resident John Bremner’s memoir, Hoy, the Dark Enchanted Island, claims the discovery of a cave in the Hamars just beyond the Dwarfie Stane, the very same place I made my spellbound climb. In it he found an egg-shaped object similar to those found at Skara Brae. Might the Neolithic residents of north Hoy have seen some special purpose to this place?

The strange stories surrounding the Dwarfie Stane have attracted visitors across cultures and eons, and no doubt it will continue to draw seekers of oddities for many years to come. Whether you believe it to be the home of dwarves or giants, or simply a muse for writers and tellers of tall tales, the Dwarfie Stane is one of Orkney’s most offbeat and inspiring treasures.

Further Reading

- Caroline Wickham-Jones. Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2019.Mark

- Mark Edmonds. Orcadia: Land, Sea and Stone in Neolithic Orkney. London: Head of Zeus Ltd., 2019.

- Tom Muir. The Mermaid Bride and other Orkney folk tales. Kirkwall: The Orcadian Limited, 1998.