The scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow in 1919 saw Orkney briefly become headline news around the world. Author and historian, Nick Jellicoe, has organised a major conference to be held in Kirkwall focusing on the scuttling and the events surrounding it. We asked him to share his thoughts on the historic moment.

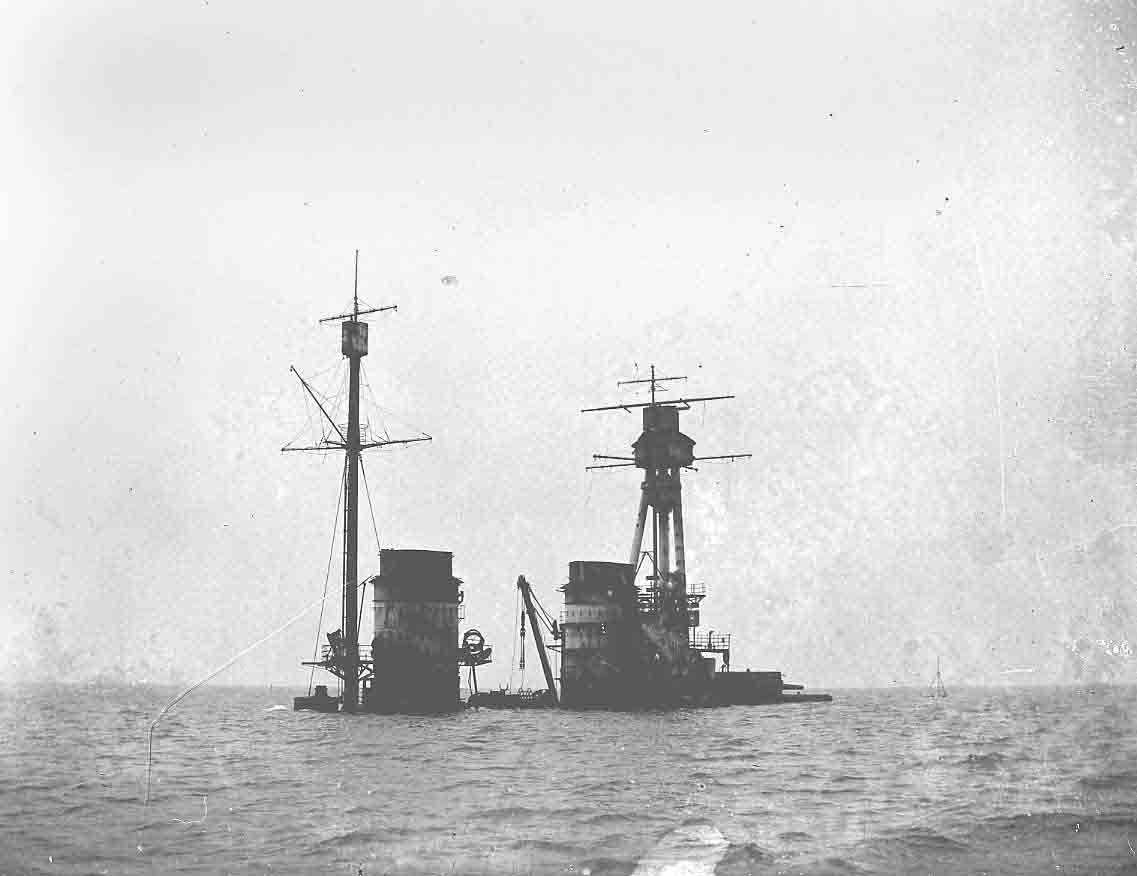

What the Grand Fleet failed to achieve at Jutland, the German Navy obligingly corrected. In a matter of hours, in June 1919, 490,000 tons of shipping went to the bottom of Scapa Flow. Overnight, the Flow became the centre of world attention.

The internment and later scuttling of the High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow was an event which divided the allies and led to some heated arguments as they gathered together to hammer out the Peace terms. It was abundantly clear that each nation had its own agenda.

The French wanted their share of the German Navy’s ships, as compensation for the immense destruction and loss of life. The country had lost 1 ½ million men, half of the male population under the age 30. The Americans, late-comers to the war, had nevertheless contributed significantly to Britain’s naval defence of the Atlantic convoys and the protection of the North Sea. But they also wanted an end to what they saw as Britain’s arrogant dominance of the world’s oceans and would have been quite happy to see other naval powers bettered if that would keep Britain in check. Destruction of the German Navy might have sounded sensible but politically impossible when, in the same breath, the politicians wanted budgets for continued naval building.

The British, like the Americans, did not necessarily want German ships. Incorporating them into the Royal Navy wouldn’t be easy. But they certainly did not want to give more ships to the French. If it was going to receive German ships, the Admiralty preferred to have them formally surrender. This neither Lloyd George nor the French were prepared to demand if it would risk the Peace being signed.

The solution that was arrived at, after the idea of destruction had been ruled out and Admiral Beatty’s argument that it be forced to surrender turned down, was that 74 of its most modern ships be interned at Scapa Flow. Since they had not surrendered, the ships were still regarded as under German sovereignty. Consequently, no guards could be posted. It would turn out to be a recipe for disaster.

On the 21st of June 1919, with the long-term future of the fleet still far from clear, the German crews took matters into their own hands, opening the seacocks and smashing internal water pipes. Despite the British managing to drive some of the ships aground, by the end of the day 54 vessels had been sent to the seabed of Scapa Flow. It was an act of defiance which enraged the allies – though in some quarters it must have been seen as having solved an intractable dilemma.

The subsequent salvaging of much of the fleet is the stuff of legend, combining ingenuity, tenacity and no small quantity of sweat and blood. The ships that remain on the seabed are one of the world’s most alluring challenges for divers. Names like SMS König, SMS Markgraf and SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm stir the soul of those whose curiosity would take them beneath the surface of Scapa Flow.

For me the fascination in this story is this: the scuttling of a Fleet that took twenty years to build was monumental enough. But it’s an event about which we no longer have eye-witnesses to talk to us, to convey the sense of fear, wonder, excitement and, even sadness that accompanied it. I want to see if we can re-discover some of those feelings over the next months, particularly with the work that I’ll be doing on an animation of the event. The challenge there will be to pass this story to another generation in their language and in the way they want to hear about it. To rekindle a sense of awe in history.

Scapa Flow’s importance for the Navy was fundamental, but the scuttle put Orkney in to the very centre of the Peace discussions in Versailles and the salvage that followed saved Orkney from the worst of the Depression.

As we look ahead to next year’s centenary, we also remember those eight German sailors who were killed that day. They were last victims of a conflict which had devastated Europe. In an atmosphere of panic and confusion, despite the white flags of surrender, they were shot for refusing to attempt to save their ships while a ninth, Kuno Eversburg, was killed in cold blood two days later on a British battleship.

Their story, and the wider story of the scuttling, deserves to be better recognised. That’s something that many of us are keen to see put right in coming months.

A two-day conference will take place at Kirkwall Grammar School on Friday 23 and Saturday 24 November focusing on the scuttling and the events surrounding it. Find out more via the official website.

Nick Jellicoe is the grandson of Admiral, the 1st Earl Jellicoe of Scapa, and author of Jutland. The Unfinished Battle. He is currently completing a book on the scuttling. The Last Days of the High Seas Fleet is currently available to pre-order.

Nick Jellicoe is the grandson of Admiral, the 1st Earl Jellicoe of Scapa, and author of Jutland. The Unfinished Battle. He is currently completing a book on the scuttling. The Last Days of the High Seas Fleet is currently available to pre-order.

The Digital Orkney project has been part financed by the Scottish Government and the European Community Orkney LEADER 2014-2020